London

CNN

—

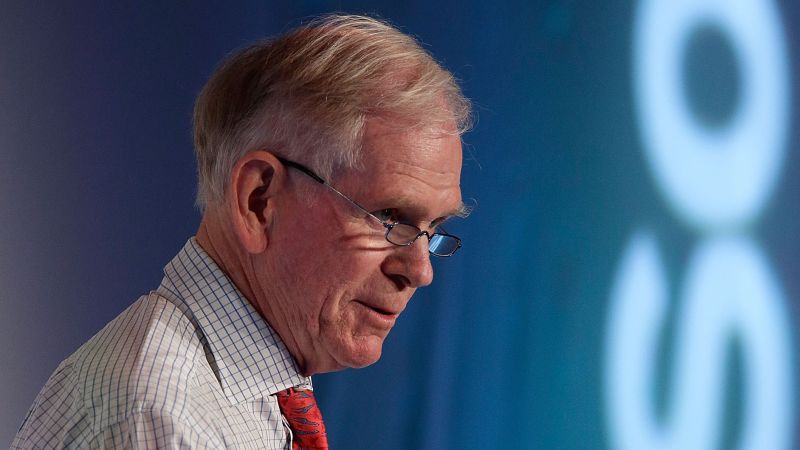

Jeremy Grantham made his name predicting the dot-com crash in 2000 and the financial crisis in 2008. Now, the famous investor warns another epic bubble in financial markets is bursting — and the turmoil that swept through the banking sector last month is just the beginning.

“Other things will break, and who knows what they will be,” Grantham told CNN in an exclusive interview. “We’re by no means finished with the stress to the financial system.”

The co-founder of investment firm GMO is known for his bearish views. A frenzy in multiple US markets spurred by rock-bottom interest rates after the coronavirus pandemic led Grantham to call “one of the great bubbles of financial history” back in 2021.

Since early 2022, when the S&P 500 hit an all-time high, US stocks have dropped about 15% as central banks have jacked up borrowing costs. But Grantham sees much steeper declines on the horizon.

The “best we can hope for,” he said, is a fall of about 27% from current levels, while the worst-case scenario would see a plunge of more than 50%. The low point might not arrive until “deep into next year,” he added.

Analysts at Bank of America and Goldman Sachs, for their part, see the S&P 500 finishing 2023 only about 2% below Wednesday’s close. Morgan Stanley foresees a drop of nearly 5%.

Stocks aren’t the only assets that notched excessive valuations when cheap money encouraged investors to take big risks. The prices of government bonds, real estate and even cryptocurrencies also shot up.

This widespread exuberance could lead to a particularly harsh reckoning, according to Grantham. The recent failure of Silicon Valley Bank, for example, was triggered in part by losses on its bond holdings as interest rates jumped and prices of US government debt fell.

As the bubble deflates, it’s all but certain to result in an economic downturn, he predicted.

“Every one of these great bursts of euphoria, the great bubbles with overpriced markets … has been followed by a recession,” Grantham said. “The recessions are mild if everybody does everything right and there [are] no complications. They are terrible if people get everything wrong.”

In the meantime, investors should “count on being surprised,” Grantham said.

It would have been difficult to predict the implosion of Silicon Valley Bank, or the need for the Swiss government to swoop in and orchestrate an emergency rescue of Credit Suisse, he explained.

“When the great bubbles break, they do impose a lot of stress on the system,” Grantham said. “It’s like pressure behind a dam. It’s very hard to know which part will go.”

The correction in the bond market may be almost complete, Grantham forecast. But stock valuations remain “way above any long-term traditional relationship” to corporate performance.

Strain in the financial system could therefore grow when, as he expects, the US economy enters a recession and corporate earnings begin to take a hit. Economists at the Federal Reserve are predicting a mild recession in late 2023 because of fallout from the banking crisis.

Even in this environment, though, there will be opportunities to make money. (GMO has a US equity fund, with holdings in companies such as Apple

(AAPL), Microsoft

(MSFT), ExxonMobil

(XOM) and Kroger

(KR).) But in the short term, “almost everybody gets hurt” as asset prices come back down to Earth, Grantham said.

Grantham sees uncomfortable parallels between markets today and 2000, when an explosion in the price of tech stocks was followed by a dizzying crash. There are also echoes of 2008, when a painful comedown in the US housing market almost broke the banking system.

What’s even more worrying is that this time, bubbles in the stock market and the real estate market are poised to burst simultaneously, Grantham said.

That’s what happened in Japan in the early 1990s, unleashing a long period of economic stagnation that haunts the world’s third-largest economy to this day.

“They have had basically a lost 20 years, and in addition a fairly lame 10 years,” Grantham said.

He added: “The occasions where people have tried to break a bubble in the stock market and the real estate market together are fairly ominous.”

Fears about the health of the US commercial real estate industry have grown in recent weeks. The sector, which relies heavily on debt financing, has been hit hard by rising interest rates. The popularity of remote work has been particularly difficult for offices, a market Grantham quipped was in “ragged disarray.”

Meanwhile, US home prices, which hit record highs in 2022, have also started to drop as mortgage rates have leaped.

Grantham blamed central bankers for the emergence of the latest market bubble in the United States. They pursued policies in recent decades that artificially drove up the value of financial assets, setting the stage for crashes, he said.

Every Federal Reserve chair since Alan Greenspan, who led the US central bank from 1987 to 2006, “has followed the same policy that lower rates are good for you,” he said. “What has it delivered? It’s delivered a series of great bubbles that then break and inflict a lot of pain.”

Jerome Powell, the current Fed chair, would be wise to follow the example of Greenspan’s predecessor, Paul Volcker, according to Grantham.

Volcker raised interest rates to unprecedented levels to fight inflation in the late 1970s and early 1980s. He succeeded in curbing price rises, though his policies also led to a series of recessions.

“If Powell could just channel a little bit of Volcker, that would be a distinct improvement,” Grantham said, suggesting that the Fed needs to stay the course on its rate hikes instead of buckling prematurely.

Consumer inflation in the United States eased to 5% in March, the lowest annual rate since May 2021. That has boosted speculation among investors that the Fed could soon stop raising borrowing costs.

But longer-term trends could prop up inflation for years to come, Grantham said.

Climate change is resulting in extreme weather and more intense and frequent natural disasters. That will disrupt the supply of commodities and raise food prices. Aging populations also pose a risk as smaller workforces command higher wages.

“These are not mild influences,” Grantham said. “These are very clear and important.”